The word restorative implies “putting back” or “regaining”. An effective supervisor helps you to restore what you need to be a fully functioning coach (which may not be that different from what you need to be a fully functioning individual, although the supervisor is not expected to be a counsellor or therapist). Coaching other people through difficult issues can be exhilarating, when we can see the immediate impacts; but it can also be deflating, when the client doesn’t seem to be making the progress we and/or their sponsor thinks they should.

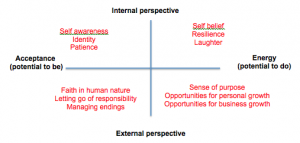

Restorative functions in coaching can be seen in terms of the matrix below, developed by one of us (David) in response to conversations with coaches about how they restore their energy and the factors that influence their readiness for coaching. A good supervisor should be capable of offering support in all these areas. To explain the two dimensions:

Perspectives – the supervisor uses their objectivity and their own experience/ knowledge to help the coach step back and gain a more balanced view of themselves and their practice. It’s all too easy to have feelings of self-doubt, or to make assumptions about the client and their world. A “helicopter” perspective acknowledges both what is happening on the ground and the bigger picture

Acceptance is about the coach’s potential to be, while energy is about potential to do. The effective supervisor helps the coach let go of unhelpful beliefs, assumptions and emotions; and to renew his or her stores of energy.

Restorative functions of an effective supervisor

The functions in the matrix are drawn from our own experiences as supervisors and as coaches being supervised, as well as from the reflections of coaches, who have contributed to our research.

Self-awareness: To restore our fitness to coach, we need to understand what emotions and assumptions may be inhibiting us. Exploring how we feel about a client relationship, for example, gives us the choice to change how we feel

Identity: Especially at the early stages as a coach, people often suffer from an identity crisis. “Who am I as a coach?” can quickly become “Who am I as a person?”. Refocusing on values and how you contribute to the world around you creates the opportunity to be more accepting of who you are and – perhaps more important – who you are becoming.

Patience: Early stage coaches also are often in a hurry to acquire experience and track record, at the expense of reflecting deeply on the what they have experienced so far. Supervision can gently restore the balance, offering calm space to refocus on being rather than doing.

Faith in human nature: Most people come to the role of coach with a generally positive view of human nature, but this can be undermined by the experiences of their clients at the hands of manipulative bosses (or by clients, who try to manipulate the coach to their own ends). Effective supervisors have had their own faith in humanity tested many times and are able to help the coach put the behaviours of a few people into perspective.

Letting go of responsibility: Of course, coaches have responsibility towards clients and their sponsors, plus of course general responsibilities towards society and the coaching profession. Once again, a balance is important. Coaches often assume far too much responsibility for what the client does (or doesn’t do) as a result of coaching conversations. They feel guilty or inadequate, if the client doesn’t emerge from a session with a clear solution, or if the intended results of coaching don’t happen. In doing so, they are in effect usurping the client’s responsibilities for their own actions. Once again, the supervisor’s restorative role is about helping the coach work out what a reasonable balance of responsibility is.

Managing endings: Coaches get lots of training in how to start an assignment and how to hold a coaching conversation. One of the things they don’t usually get is training in how to deal with disengagement from the client. The closer and more intimate the relationship with the client has been, the harder to just walk away. Yet the coach must avoid creating dependency by prolonging the assignment. As they become more mature, coaches also bring to supervision issues of moving on within their business arrangements, as they outgrow commercial relationships, which seemed right before.

Self-belief: When things don’t work out as the coach feels they should have, the effective supervisor helps shift focus from self-blame to learning from experience. They help the coach remember and appreciate what they are like at their best and reflect upon how to make their norm more like their best.

Resilience: Coaches need coping strategies to back up after a knock-down. The supervisor provides both empathy and practical support in developing and applying such strategies.

Laughter: The ability of laughter to restore energy has been demonstrated in numerous clinical studies. (Freud analysed the mechanisms and impact of laughter 100 years ago!) Good supervision helps the coach to see the absurdity in complex situations (so putting them in perspective) and to laugh at themselves.

Sense of purpose: Most coaches go through periods of questioning why they are coaches. Supervision helps reconnect with your core values and aspirations – which are a key resource for recharging our internal batteries and rediscovering our enthusiasm.

Opportunities for personal growth: Having a sense of becoming better and better as a coach is an important self-motivator, but we are not always conscious of the progress we are making. Supervision helps us see how we are developing and identifies learning opportunities that align with our sense of purpose.

Opportunities for business growth: The skills of being a great coach and running a great business don’t necessarily go together. Again, effective supervision brings perspective and helps coaches achieve a balance of attention between their personal authenticity and the needs of their business.

© David Clutterbuck 2015

Newsletter Signup

Newsletter Signup Sign Up For a Free Trial

Sign Up For a Free Trial